For the past three years, I have been working on a novel called The Crimson Thread, a reimagining of the Minotaur in the Labyrinth myth set in Crete during the Second World War.

I’ve been fascinated by the story of the minotaur ever since I read Tales of the Greek Heroes by Roger Lancelyn Green, when I was about fourteen. I found an old copy of the book shoved up in a top cupboard in my grandparents’ house one boiling hot summer when I was staying with them during the school holidays. In brief, the myth goes like this:

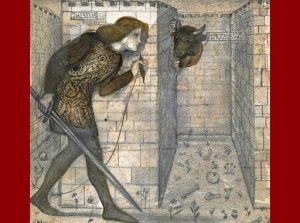

Every seven years, Athens had to send seven youths and seven maidens to Crete to be fed to the minotaur, a bull-headed man who was kept locked in a vast labyrinth. No-one had ever escaped. One year, Theseus, the prince of Athens, volunteered to go in the hope that he could kill the minotaur and so free his city from the sacrificial tribute. Once in Knossos, the Cretan princess Ariadne fell in love with Theseus, and offered to help guide him through the labyrinth. She gave him a ‘clue of thread’ and told him to fasten one end to the door of the labyrinth. Theseus then ‘traced his way through the winding passages, leading up and down, hither and thither, until he came to the great … cavern in the centre … where the monster (was) waiting for him.’

Edward Burne-Jones, ‘Theseus and the Minotaur’, ink and pen drawing (1861)

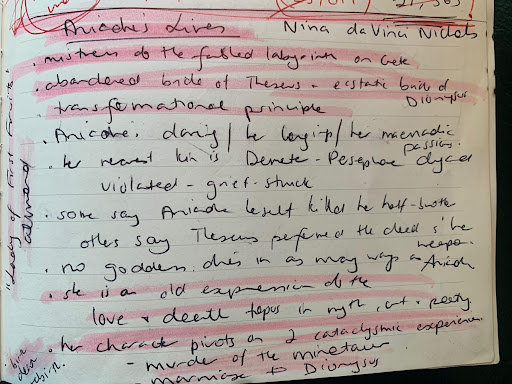

Theseus slaughters the minotaur and follows the thread out of the labyrinth, and then he and Ariadne flee Crete and her father’s wrath. But Theseus then betrays Ariadne and abandons her, and Dionysus, the god of wine and ecstasy and epiphany, falls in love with ‘her wild, dark beauty’ and weds her, making her immortal. Her crown of stars is flung up into the heavens, and becomes the Coronoa Borealis, a navigational aid to help those who are lost.

In the version I read as a child, Theseus does not abandon her willingly, but that is because - for Roger Lancelyn Green – Theseus is the hero and so should not behave so callously. Another detail that Green left out is that the minotaur is Ariadne’s half-brother.

I don’t know why this ancient myth struck me so forcibly. Perhaps because it was the only story in the book where a girl has an instrumental role to play. It is not the hero Theseus who solves the puzzle of how to escape from the labyrinth, it is Ariadne. He is simply doing her bidding.

The minotaur in the labyrinth is a very old tale, older even than ancient Greece, because its roots lie in the bull-dancing culture of the Minoan civilisation that existed in Crete from around 2000 BCE. The ruined palace of Knossos – which is where my story is centred – has evidence of this in its frescoes and artefacts.

The Bull-Leaping Fresco, c. 1450 BC

Bull-leaper bronze figurine, c. 1600 BC

The Palace of Knossos was so famous as the source of the minotaur in the labyrinth myth, that the symbol is depicted on its ancient coins.

Silver tetradrachm, Knossos, Crete. 2nd-1st century BCE.

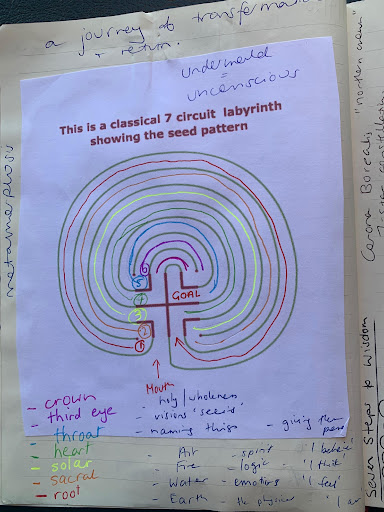

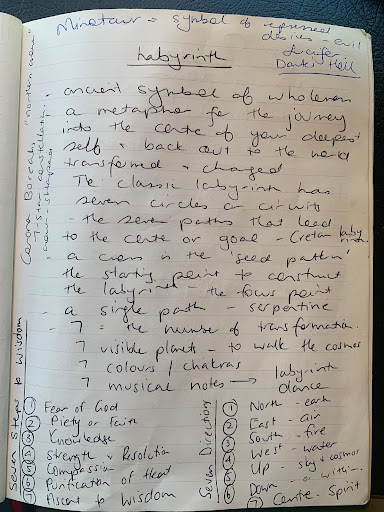

Both Freud and Jung were fascinated with the labyrinth as a symbol of the unconscious mind. In his book ‘Man and His Symbols’ (which I first read when I was sixteen), Jung wrote: ‘The maze of strange passages, chambers, and unlocked exits in the cellar recalls the old Egyptian representation of the underworld, which is a well-known symbol of the unconscious … It also shows how one is “open” to other influences in one’s unconscious shadow side and how uncanny … elements can break in.’

So when we walk the labyrinth we journey to that deep dark place hidden within us, and face our shadow side.

I have always found it so interesting that our word ‘monster’ comes from the Latin verb monere which means ‘to warn’ and the Latin noun monstrum which means ‘an evil omen’. Other words that come from the same root are ‘monitor’ (someone who warns), ‘admonition’ (to express disapproval), ‘premonition’ (a forewarning), demonstrate (to show or reveal) and remonstrate (to prove through argument or pleading) and – less obviously – ‘summon’, which originally meant to admonish or warn secretly.

Monsters have haunted the human imagination from the beginning of our history, manifesting our fears and desires and urges, particularly those we repress most deeply. They appear most commonly in stories – in our myths and legends and fables, our dramas and novels and films. This is because storytelling is the most effective tool we have to process the terrors of the night. Monsters give us a way to embody and examine these fears. Monsters are metaphors for thinking with.

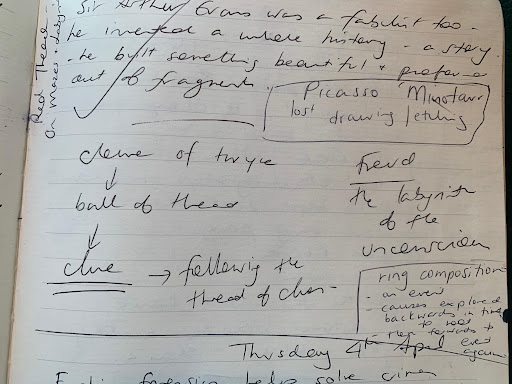

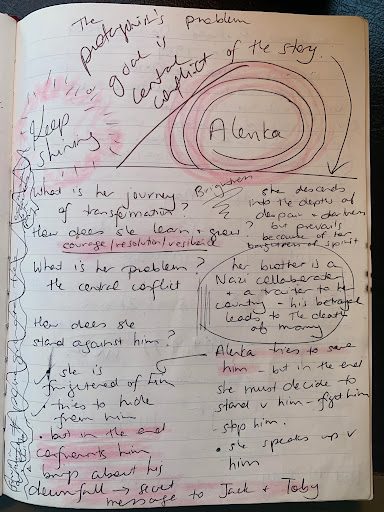

Here are a few pages from my notebook that show me working out some of my thoughts about minotaurs and labyrinths, and my protagonist’s own journey to the underworld and back.

The Crimson Thread will be released by Penguin Random House Australia in July 2022.